Paper Review: Test Coverage in Python Programs

Link to paper

Intro

Recently a friend suggested I combine my interests in software engineering and academia and check out the work of Prem Devanbu. Prem is a Professor at the University of California at Davis and a co-director of the DECAL Lab. Among other things, Prem analyzes both the processes of software development, and the code it produces.

I’m excited by this new topic! The beauty I find software development is that at its best it is exponential. People don’t just write software, they write software to help them write software, and software to help them write that. I find the thrill of accelerating my creative process addicting. I am always looking for new IDEs, obscure programming languages, and methodologies. Today’s paper covers one of the most popular catalyst’s for in software development: the humble unit test.

In 2019 Prem Devanbu, Casey Casalnuovo, and Hongyu Zhai published their paper “Test Coverage in Python Programs”. This paper takes a look at three of the most popular open source Python projects, and examines the code coverage of their integrated unit tests.

For the uninitiated, a unit test is a chunk of code designed to test the function of a piece of software you’re developing. For example if you’re creating a calculator, you might write a unit test to ensure asking 5 * 5 produces 25, and asking 5 / 0 produces a well formatted message kindly reminding the user one can not devide by 0. For convenience, unit tests are generally written in the same language as the software being tested and are stored in the same repository. Many libraries are available to make reading unit tests easier.

Although it’s outside the scope of this blog post, there is an interesting software development methodology called test-driven development, which as the name suggests builds software from the ground up based on testing it’s functionality.

One important concept when it comes to unit testing is “code coverage”. Code is “covered” when it is run during a test. So the code coverage of a project is the subset of its code that is tested by its unit tests.

A basic question you can ask about a project is: what percentage of the code is covered? The higher the percent, the less opportunity there is for unintended behavior to slip in in uncovered code. This has already been a research topic, and most unit testing libraries provide tools to see projects coverage percentages.

Prem’s paper go’s further to ask “In general, what parts of a code base are uncovered?”.

The Paper

(I am simplifying the paper and methodology quite a bit, check out the full paper for the details.)

To answer this question, the team looked at 4 major open source python projects:

- Flask

- Matplotlib

- Pandas

- Scikit-learn

- Scrapy

Then for each statement in the projects (for which the information was available) they noted:

- Whether the statement was covered

- The “depth” of the statement in the code

- The type of the statement (If, Assert, ExceptHandler, etc.)

- How long ago the line was written

- The line number

1. Was obtained using a service called Codecov, that tracks code coverage for the five projects they analyzed.

2. and 3. Were obtained using the python Library “ast”. AST Stands for abstract syntax tree and refers to the lower-level language python “compiles” into right before running. This language takes the form of a tree, with the depth of a statement represented by its depth in the tree. Furthermore the nodes of the tree are marked with the types of the source statements.

4. Was found using Git, a very popular file versioning tool.

5. Was found by, well, counting the lines.

They then used a logistic regression model[5] to model a statement’s chance of being covered (1.) based on (2.) - (5.).

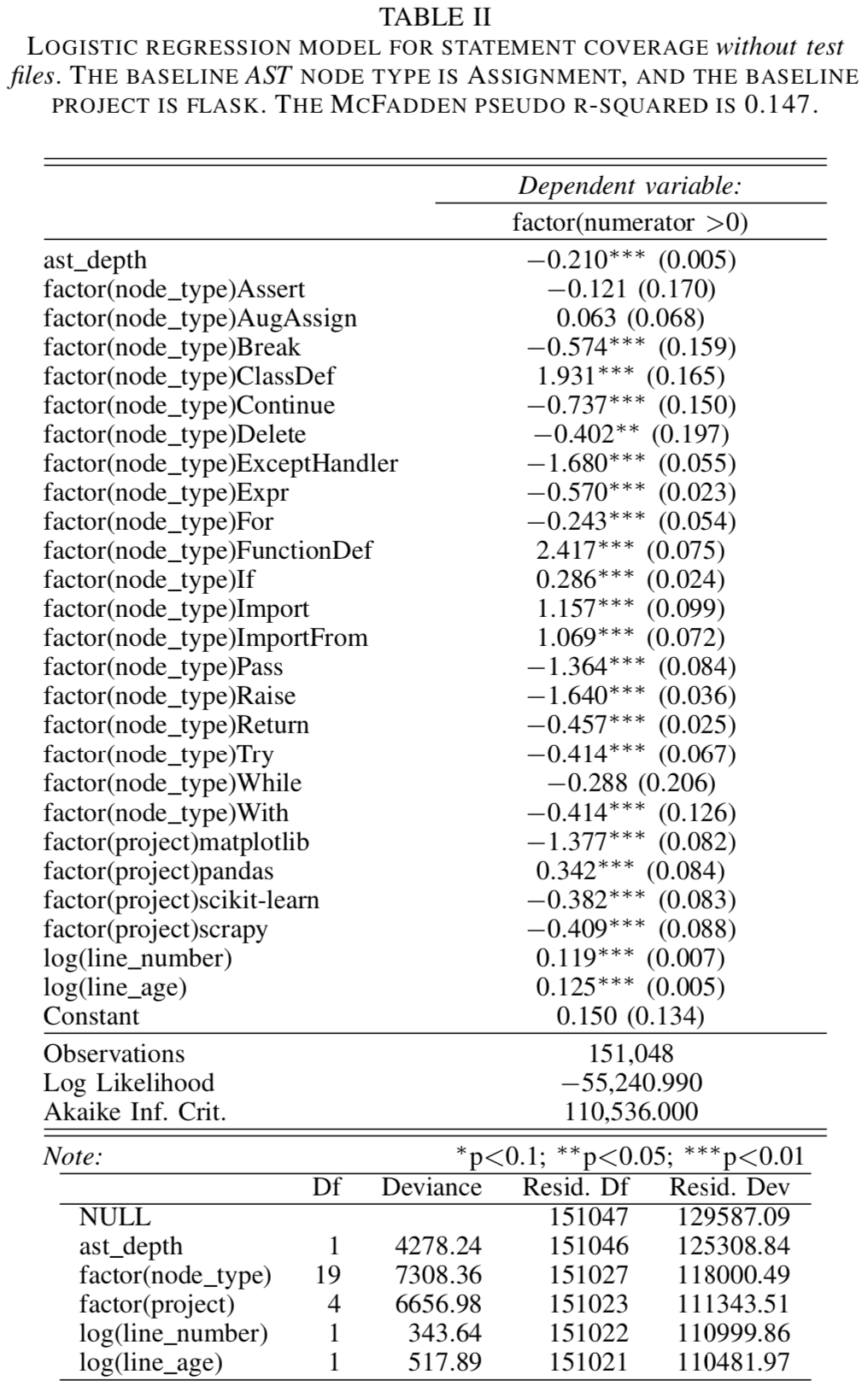

The results are summarized in their table II:

The first thing to understand about this table is that the “Dependent Variable Factor” is on a logarithmic scale, so we need to plug it into 1-e^x in order to extract its meaning.

For example with ast_depth: 1-e^(-0.210) = 0.1894.

Now to interpret the values:

For ast_depth, 1-e^(-0.210) = 0.1894 means that for every layer of depth a statement is, it gets 18.94% less likely to be covered.

For node_type factors, The authors compared the probability of each node type being covered against a baseline type, assignment. ( x = 3 is an example of an assignment).

So a “For” type statement is 1-e^(-0.243) = 0.2157 = %21.57 less likely to be covered then an assignment.

A “If” type statement is 1-e^(0.286) = -0.3311 = -%33.11 less likely to be covered then an assignment. note this percentage is negative, so really A “If” type statement is %33.11 more likely to be covered then a assignment.

A “Exception Handler” type statement is 1-e^(-1.680) = 0.8136 = %81.36 less likely to be covered then an assignment.

And so on.

The authors point out the results on the effect of the depth of a statement and whether the statement is an Exception Handler has on its chance of being covered as important.

Analysis

Unit testing is a powerful technique. While working as a intern for 1010Data, it helped me in two ways:

- Caching bugs and newly broken code as I implemented new features and fixed old ones.

- Helping me understand the problem deeper as I wrote new unit tests.

These two features worked in harmony as I used test-driven development. This means I would write tests for a certain problem before the code to solve it. The tests I found hardest to write were one that required lots of setup to even get the program into a state where it could perform what I was testing.

This paper validates that experience since two of the categories of code that requires the most setup to test are:

- Code that is deep in the syntax

- Code that handles exceptions

Code that is deep in syntax requires setting a whole host of variables so the code pointer can even make it past the various if and switch statements. As for exceptions, I found I had to make modifications to the simulation environment chest to push the code to break. For example I had to create a fake database in order to test database read and write exception handling.

It makes sense then that unit tests that are harder to write are also the ones that are written less. Furthermore, the less time and energy a company wants to put into unit testing, the more these harder to test statements will be missed. The fallacy people think is “if a line of code is hard to test, it must not run frequently, and so it is not as important as lines that are easy to test”.

One solution to this is to construct more powerful unit testing tools and libraries, which features targeting exception handling and deep statements. For example, a program that upon selecting a line in an IDE will generate a boilerplate unit test that runs that line. Then the programmer needs only to enter the expected output. This can help with deeply nested statements.

Making exception handling testing easier requires a greater focus on the environment in which you test your program. The Python Library “mock” is already powerful enough for this, so maybe a rapper to allow using it in fewer lines or making it simpler would be effective.

In any case this paper was very interesting. I’m really excited to see other ways that software engineering can be studied from an academic perspective.